Crisis after crisis seems to be the way the world operates at the moment. It is not surprising that all of these is affecting the way supply chains behave. We spoke with Kamala Raman, VP Team Manager, Supply Chain Research about why supply chains are moving, what it takes to do it well, where they going and more. Read more from our September Digital Magazine now!

What are the reasons supply chains are diversifying right now?

The 2022 Gartner Globalization Trends in Designing Supply Chain Network Survey shows that 74% of respondents have made changes to the size and number of locations in their global supply chain networks in the last two years.

Unsurprisingly, in a time of inflationary pressures on everything from material costs to labor to transportation costs, reducing operational expenses is one of the top drivers of this network change. Other drivers include increasing regional or local supply bases for better resilience, meeting sustainability objectives and simplifying the network. Resilience and sustainability objectives drove more of the change in European respondents.

APAC respondents focused on cost-efficiency and setting up for future growth. North American respondents prized cost-efficiency and regulatory requirements slightly over other needs.

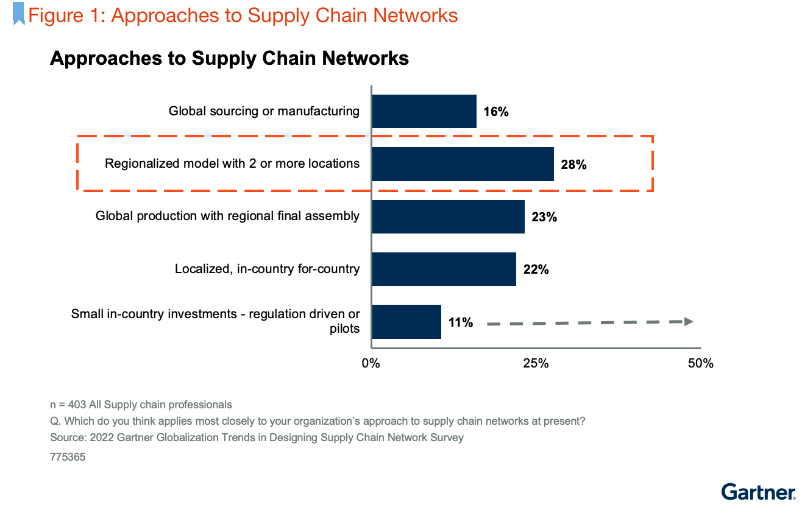

The resulting networks span a variety of operating models. A hybrid regional approach emerges as the most common design. This is closely followed by global models using postponement and local-for-local networks (see Figure 1).

How expensive is the whole process and would costs be sent down the supply chain?

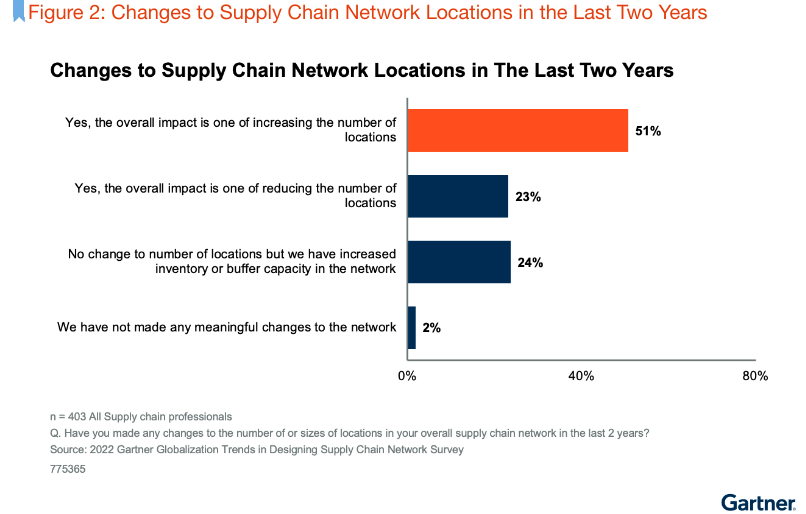

The process can indeed be time and money intensive and impacts not only their own factories but partners up and down the ecosystem. Supply chain leaders have been modifying networks in a number of ways, whether it was their own or contracted locations with expansions, consolidations or the reliance on modifications to buffers, which are more reversible than footprint decisions (see Figure 2).

When questioned on where the largest changes to their supply chains have been over the last two years, increasing buffer capacity was the leader (27%), closely followed by supplier diversification (24%), with 12% modifying the number of contracted locations and only 7% modifying their own production locations. It is indeed far easier to modify capacity or inventory than to add physical factories.

What products/manufacturing facilities are most likely to be relocated?

Even in the face of a pressing need for resilience, it is extremely difficult to effect dramatic and extensive changes very rapidly in supply chains designed for cost-efficiency. Ongoing constraints in global supply chains may be a strong incentive for localizing or regionalizing sourcing or production networks. However, with economic uncertainty and constraints on labor availability in developed markets, it is not clear that organizations are willing to unravel efficient global supply chains with sophisticated and capable partners around the globe without strong government mandates.

Capex light industries have already made many changes (such as in apparel or shoes or furniture making). Capex heavy industries naturally are looking to utilize existing assets as well as they can while still diversifying for resilience. And highly regulated industries (life sciences, semiconductors etc) will have to move more piecemeal and more slowly. Ie. TSMC may announce one chip factory in Arizona but their broad ecosystem will still lie in Taiwan.

Is Asia the biggest winner? How about locations in Eastern Europe and Latin America?

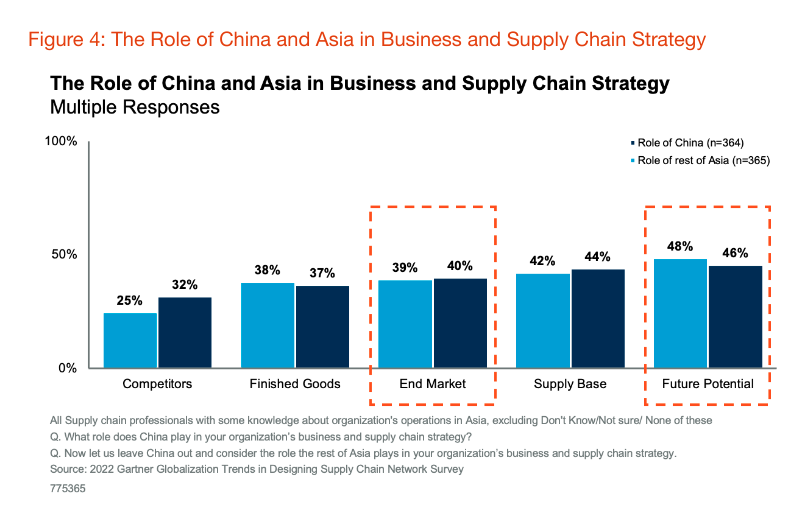

Survey respondents made it clear that China, as well as the rest of Asia, will continue to be key to their present as well as future networks, particularly as supply bases and future markets. Given that the diversification away from China is happening in small trickles as well as larger moves, many countries in the rest of Asia have been beneficiaries — especially when it comes to scoring net new foreign direct investments.

The emergence of a regionalized Asian network (“in Asia, for Asia”) driven by coordinated industrial policies, such as the implementation of the RCEP trade deal, showed up in the survey with 60% of the APAC respondents pointing to their home region’s importance not only as a supply base but as an end market (see Figure 4).

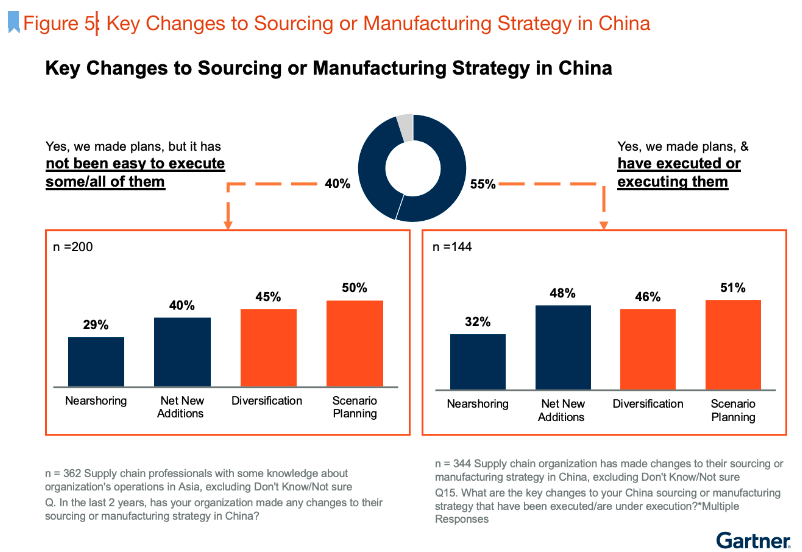

Additionally, roughly 40% of those respondents who have made plans to change their China sourcing and manufacturing strategy indicated that it has not been easy to execute some of the planned changes (see Figure 5).

The survey also points to the difficulty of making long-term capital investments for small or midsize firms that vastly prefer reversible inventory buffers or supplier diversification to establishing their own footprint in more expensive locations. The signs are clear that in a fragmented world, global firms have begun making inroads into their heavily cost-optimized,

one-size-fits-all networks with a mix of global, regional or local elements utilized. Investments into other parts of Asia (outside of China) coexist with expanded investments into developed markets as organizations take advantage of generous national/trade-bloc-level trade incentives in the name of national security. We will be watching for whether these changes will gather steam or fizzle out as global economies show signs of slowing down. ✷